Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products

This book is a solid primer on habit formation, mostly focused on digital products. Some of the examples are a bit dated, but it’ll teach you how to think about building stickier, more engaging products.

What Are Habits?

Cognitive psychologists define habits as “automatic behaviors triggered by situational cues”—things we do with little or no conscious thought.

Neuroscientists believe habits give us the ability to focus our attention on other things by storing automatic responses in the basal ganglia, an area of the brain associated with involuntary actions.

First to mind wins. A habit is at work when users feel a tad bored and instantly open Twitter. They feel a pang of loneliness and before rational thought occurs, they are scrolling through their Facebook feeds. A question comes to mind and before searching their brains, they query Google.

The Hook Model

Through consecutive Hook cycles, successful products reach their ultimate goal of unprompted user engagement, bringing users back repeatedly, without depending on costly advertising or aggressive messaging.

1. Trigger

A trigger is the actuator of behavior—the spark plug in the engine. Triggers come in two types: external and internal. Habit-forming products start by alerting users with external triggers like an e-mail, a Web site link, or the app icon on a phone.

When users start to automatically cue their next behavior, the new habit becomes part of their everyday routine.

2. Action

Following the trigger comes the action: the behavior done in anticipation of a reward.

Companies leverage two basic pulleys of human behavior to increase the likelihood of an action occurring: the ease of performing an action and the psychological motivation to do it.

3. Variable Reward

Research shows that levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine surge when the brain is expecting a reward. Introducing variability multiplies the effect, creating a focused state, which suppresses the areas of the brain associated with judgment and reason while activating the parts associated with wanting and desire.

4. Investment

The investment phase increases the odds that the user will make another pass through the Hook cycle in the future. The investment occurs when the user puts something into the product or service such as time, data, effort, social capital, or money.

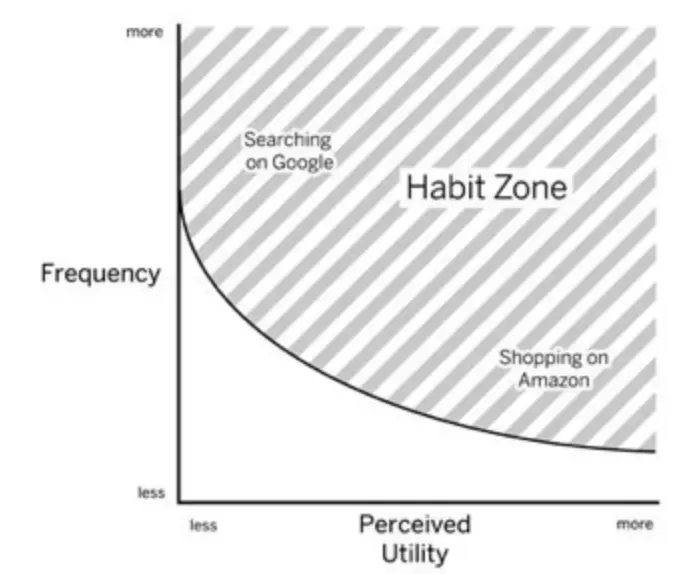

The Habit Zone

For an infrequent action to become a habit, the user must perceive a high degree of utility, either from gaining pleasure or avoiding pain.

A company can begin to determine its product’s habit-forming potential by plotting two factors: frequency (how often the behavior occurs) and perceived utility (how useful and rewarding the behavior is in the user’s mind over alternative solutions).

Research has not found a universal timescale for turning all behaviors into habits. A 2010 study found that some habits can be formed in a matter of weeks while others can take more than five months.

Why Habits Matter for Business

Customer Lifetime Value (CLTV): Fostering consumer habits is an effective way to increase the value of a company by driving higher customer lifetime value—the amount of money made from a customer before that person switches to a competitor, stops using the product, or dies.

Pricing Power: Warren Buffett once said, “You can determine the strength of a business over time by the amount of agony they go through in raising prices.” Habits give companies greater flexibility to increase prices.

Growth Through Retention: In Evernote’s “smile graph,” although usage plummeted at first, it rocketed upward as people formed a habit of using the service. After the first month, only 0.5 percent of users paid for the service; by month thirty-three, 11 percent had started paying.

Viral Growth: As David Skok points out, “The most important factor to increasing growth is Viral Cycle Time.” Users who continuously find value in a product are more likely to tell their friends about it.

Competitive Moats

A classic paper by John Gourville stipulates that “many innovations fail because consumers irrationally overvalue the old while companies irrationally overvalue the new.”

For new entrants to stand a chance, they can’t just be better—they must be nine times better. Because old habits die hard and new products or services need to offer dramatic improvements to shake users out of old routines.

Users also increase their dependency on habit-forming products by storing value in them—further reducing the likelihood of switching to an alternative. Switching to a new e-mail service, social network, or photo-sharing app becomes more difficult the more people use them.

Behaviors are LIFO: Experiments show that lab animals habituated to new behaviors tend to regress to their first learned behaviors over time. “Last in, first out.”

Vitamins vs. Painkillers

Painkillers solve an obvious need, relieving a specific pain, and often have quantifiable markets. Vitamins, by contrast, appeal to users’ emotional rather than functional needs.

A habit is when not doing an action causes a bit of pain.

Habit-forming technologies are both vitamins and painkillers. These services seem at first to be offering nice-to-have vitamins, but once the habit is established, they provide an ongoing pain remedy.

Triggers

External Triggers

External triggers are embedded with information, which tells the user what to do next.

Types of External Triggers:

-

Paid Triggers - Advertising, SEM, etc. Unsustainable for reengagement; generally used to acquire new users.

-

Earned Triggers - Press, viral videos, featured app placements. Difficult and unpredictable to maintain.

-

Relationship Triggers - Word of mouth, sharing. Requires building an engaged user base enthusiastic about sharing benefits.

-

Owned Triggers - App icons, newsletters, notifications. These prompt repeat engagement until a habit is formed.

Internal Triggers

Internal triggers manifest automatically in your mind. Connecting internal triggers with a product is the brass ring of consumer technology.

Emotions, particularly negative ones, are powerful internal triggers and greatly influence our daily routines. Feelings of boredom, loneliness, frustration, confusion, and indecisiveness often instigate a slight pain or irritation and prompt an almost instantaneous and often mindless action to quell the negative sensation.

The ultimate goal of a habit-forming product is to solve the user’s pain by creating an association so that the user identifies the company’s product or service as the source of relief.

As Evan Williams said, the Internet is “a giant machine designed to give people what they want.” People just want to do the same things they’ve always done.

Finding Internal Triggers

You’ll often find that people’s declared preferences—what they say they want—are far different from their revealed preferences—what they actually do.

The Five Whys Method: Ask “Why?” as many times as it takes to get to an emotion (usually by the fifth why).

Example for email:

- Why #1: Why would Julie want to use e-mail? → So she can send and receive messages.

- Why #2: Why would she want to do that? → To share and receive information quickly.

- Why #3: Why does she want to do that? → To know what’s going on in the lives of her coworkers, friends, and family.

- Why #4: Why does she need to know that? → To know if someone needs her.

- Why #5: Why would she care about that? → She fears being out of the loop.

Action

Fogg posits that there are three ingredients required to initiate any and all behaviors:

- The user must have sufficient motivation

- The user must have the ability to complete the desired action

- A trigger must be present to activate the behavior

B = MAT (Behavior = Motivation + Ability + Trigger)

Why Actions Don’t Happen

Imagine a time when your mobile phone rang but you didn’t answer it:

- Phone buried in a bag → difficult to reach (ability)

- Thought it was a telemarketer → lack of motivation

- Ringer was silenced → no trigger

Motivation

Fogg states that all humans are motivated to:

- Seek pleasure and avoid pain

- Seek hope and avoid fear

- Seek social acceptance and avoid rejection

While internal triggers are the frequent, everyday itch experienced by users, the right motivators create action by offering the promise of desirable outcomes.

Ability: Simplicity as a Function of Scarcest Resource

In Something Really New, Denis J. Hauptly deconstructs innovation: understand the reason people use a product, lay out the steps the customer must take, then simply start removing steps until you reach the simplest possible process.

Any technology or product that significantly reduces the steps to complete a task will enjoy high adoption rates.

Evan Williams on his approach to building Blogger and Twitter: “Take a human desire, preferably one that has been around for a really long time… Identify that desire and use modern technology to take out steps.”

Fogg’s Six Elements of Simplicity:

- Time - How long it takes to complete an action

- Money - The fiscal cost of taking an action

- Physical effort - The amount of labor involved

- Brain cycles - The level of mental effort and focus required

- Social deviance - How accepted the behavior is by others

- Non-routine - How much the action matches or disrupts existing routines

Designers should ask, “What is the thing that is missing that would allow my users to proceed to the next step?”

Motivation vs. Ability: Which First?

For companies building technology solutions, the greatest return on investment generally comes from increasing a product’s ease of use.

Influencing behavior by reducing the effort required to perform an action is more effective than increasing someone’s desire to do it. Make your product so simple that users already know how to use it, and you’ve got a winner.

Heuristics That Influence Perception

The Scarcity Effect: The appearance of scarcity affects perception of value. Amazon shows “only 14 left in stock” or “only three copies remain.”

The Framing Effect: As the price of wine increased in studies, so did participants’ enjoyment of the wine.

The Anchoring Effect: People often anchor to one piece of information when making a decision.

The Endowed Progress Effect: A phenomenon that increases motivation as people believe they are nearing a goal.

Variable Reward

The startling results showed that the nucleus accumbens was not activating when the reward was received, but rather in anticipation of it. What draws us to act is not the sensation we receive from the reward itself, but the need to alleviate the craving for that reward.

Adding variability increased the frequency of intended actions (Skinner’s pigeon experiments). More recent experiments reveal that variability increases activity in the nucleus accumbens and spikes levels of dopamine, driving our hungry search for rewards.

Three Types of Variable Rewards

1. Rewards of the Tribe

Our brains are adapted to seek rewards that make us feel accepted, attractive, important, and included.

Bandura determined that people who observe someone being rewarded for a particular behavior are more likely to alter their own beliefs and subsequent actions.

2. Rewards of the Hunt

The need to acquire physical objects, such as food and other supplies that aid our survival, is part of our brain’s operating system.

During persistence hunting, the runner is driven by the pursuit itself; this same mental hardwiring provides clues into the source of our insatiable desires today.

3. Rewards of the Self

Personal gratification, mastery, completion, and competency.

Mailbox delivers something other e-mail clients do not—a feeling of completion and mastery by giving users the sense they are processing their in-box more efficiently.

Multiple Reward Types

The most habit-forming products utilize one or more of the three variable rewards types.

Email utilizes all three:

- Tribe: Social obligation to respond, desire to be seen as agreeable

- Hunt: Information about opportunities or threats to material possessions and livelihood

- Self: Task of sorting, categorizing, and acting to eliminate unread messages

Investment

In the tooth-flossing study, the frequency of a new behavior is a leading factor in forming a new habit. The second most important factor is a change in the participant’s attitude about the behavior.

A psychological phenomenon known as the escalation of commitment makes our brains do all sorts of funny things.

The more users invest time and effort into a product or service, the more they value it. There is ample evidence to suggest that our labor leads to love.

The IKEA Effect

In the origami study, those who made their own origami animals valued their creation five times higher than outside valuations, and nearly as high as expert-made origami.

By asking customers to assemble their own furniture, IKEA customers adopt an irrational love of the furniture they built.

Consistency with Past Behaviors

Little investments, such as placing a tiny sign in a window, can lead to big changes in future behaviors.

Cognitive Dissonance

In Aesop’s fable, the fox that can’t reach the grapes decides they must be sour anyway.

As Jesse Schell said: “Anything you spend time on, you start to believe, ‘This must be worthwhile. Why? Because I’ve spent time on it!’”

Skill Acquisition

Once users have invested the effort to acquire a skill, they are less likely to switch to a competing product.

Ethics: The Manipulation Matrix

To use the Manipulation Matrix, the maker needs to ask two questions:

- “Would I use the product myself?”

- “Will the product help users materially improve their lives?”

Four Types of Creators:

- Facilitators - Use their own product and believe it can materially improve people’s lives

- Peddlers - Believe their product can improve people’s lives but don’t use it themselves

- Entertainers - Use their product but don’t believe it can improve people’s lives

- Dealers - Neither use the product nor believe it can improve people’s lives

Choice Architecture

As Thaler, Sunstein, and Balz describe, choice architecture should be “used to help nudge people to make better choices (as judged by themselves).”

This book teaches innovators how to build products to help people do the things they already want to do but, for lack of a solution, don’t do.

As Paul Graham writes, “Unless the forms of technological progress that produced these things are subject to different laws than technological progress in general, the world will get more addictive in the next 40 years than it did in the last 40.”

Questions to Answer When Building Habit-Forming Products

- What habits does your business model require?

- What problem are users turning to your product to solve?

- How do users currently solve that problem and why does it need a solution?

- How frequently do you expect users to engage with your product?

- What user behavior do you want to make into a habit?

Technology Waves

Mike Maples Jr. likens technology to big-wave surfing: “Every decade or so, we see a major new tech wave.”

Technology waves follow a three-phase pattern:

- Infrastructure - Advances that enable a large wave to gather

- Enabling technologies and platforms - Create the basis for new applications that cause massive penetration and customer adoption

- Crest and subside - Making way for the next gathering wave